DOSSIER DE PRESSE

Recherche

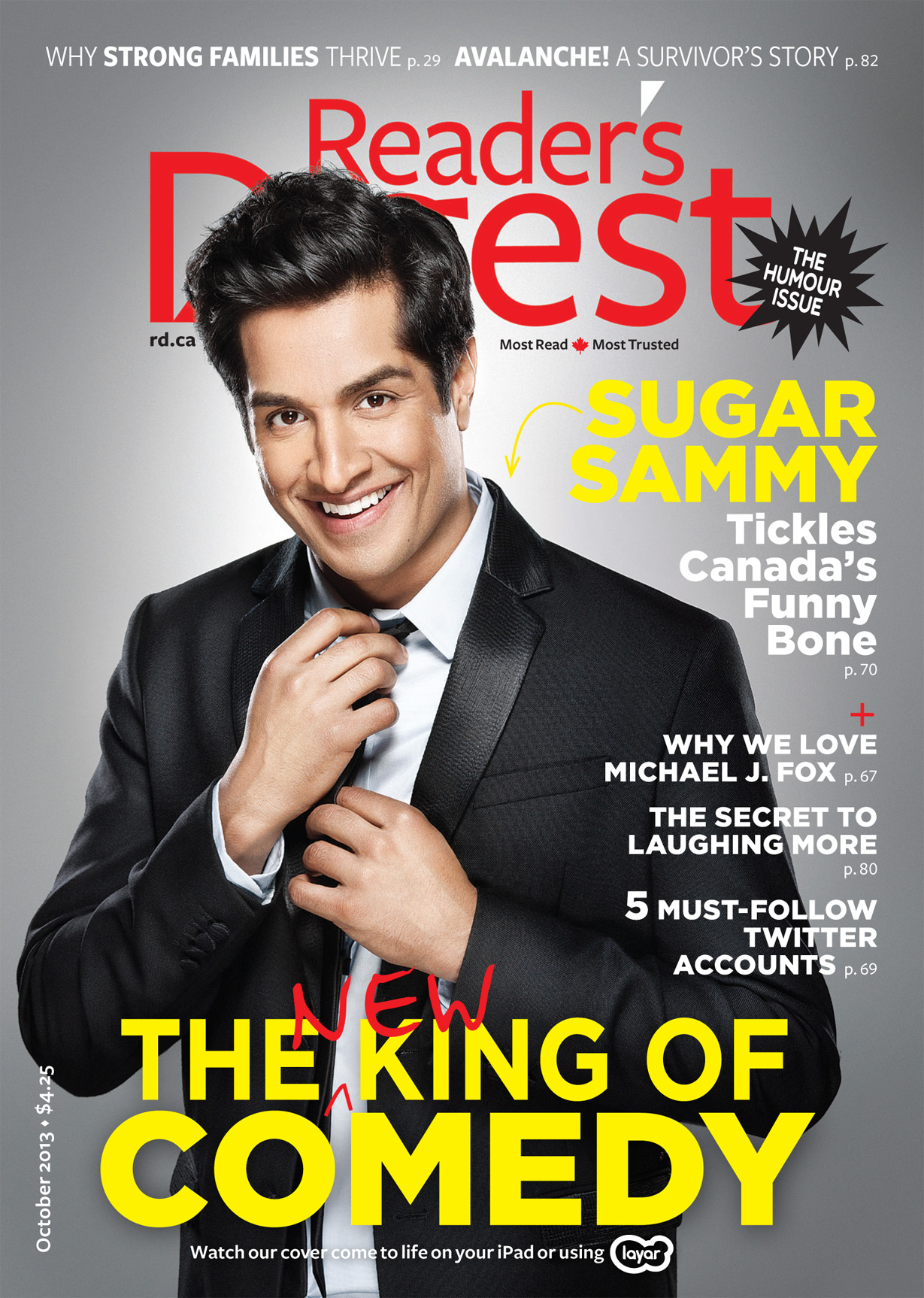

Sugar Sammy: The New Face Of Canadian Comedy

The studio sits in a warehouse in the shadow of Montreal's Autoroute 720. The neighbourhood, a holdout against gentrification, is on the cusp of big change. Big change is something that the man sitting under the lights knows a bit about. In May, he became the first non-francophone to win the top honour at Quebec's French-language comedy awards. He spent June and July writing his debut sitcom, and now August is about shooting from dawn until dusk. Soon he'll start hitting open mic nights, at least two a week, to workshop material for an upcoming Canadian tour. But today, at least, is easy: sleep in, hit the gym and now this. Sugar Sammy is getting his picture taken.

Sammy stands with his back to the camera. He pivots around and freezes with his head slightly cocked, strong jaw jutting. Thick, perfectly coiffed jet-black hair. Clean-cut good looks. Loosely knotted necktie. A tuxedo-ish jacket hugging his 37-year-old, six-foot-four frame. It's all very suave. Too much so.

“Sam,” calls out the photographer, “pas trop James Bond, eh?” Sammy slouches his broad shoulders, drops his chin, then fixes the camera with a big-eyed pout. He blows kisses. He shapes his hands into a heart. It's a little taste of why the ladies nicknamed Samir Khullar “Sugar” during his undergraduate nights as a party doorman. He's the nice boy next door. It would be easy to forget that this boy's got a mouth on him.

“Whenever I write a joke for someone else, they say, ‘This doesn't sound good coming from me,'” he says. “I guess a lot of people can't get away with saying what I get away with.”

Indeed.

Here's Sammy on clearing airport security, post-9/11: “People see me and they run back and hug their families one last time.”

On not seeing many fellow Indo-Canadians in his audience: “I guess this show's not on Groupon.”

On women: “I'm a gentleman, so I always say, ‘Why don't we split the bill? And if we sleep together, I'll refund you.'”

On men: “How can you know you're not gay if you haven't tried it? My rule is: you try 10 gay guys, and if you like six, you're gay. I liked four, so I'm straight.”

Sammy worked the Montreal comedy clubs for years. By 2004, he'd expanded to weekly sets in Ottawa. Two years later, he was touring Canada as part of The A-List, a group of up-and-coming Asian-Canadian comedians, and had landed his first gig at Winnipeg's comedy festival. He snagged the prestigious Discovery of the Festival title at the 2009 Juste pour rire gala in his hometown, earning him a coveted spot on the Hollywood Reporter's list of the top 10 rising comedy talents.

But what made Sugar Sammy a bona fide star was You're Gonna Rire, his 2011 show that he performed in both official languages. Not a French show for francophones and a separate English show for anglophones, but one show for everyone. (In an irreverent nod to the '95 referendum vote, he billed the content as “50.5 per cent English, 49.5 per cent French.”) Producers scoffed when Sammy pitched it. But he knew it would work, and with good reason: he'd already tested “franglais” material in small clubs—and it killed. He started his own production company, SugarNation, out of necessity. You're Gonna Rire would go on to sell more than 60,000 tickets in Montreal-area theatres. To put that number in context, Russell Peters, who has set comedy concert attendance records in Australia and the U.K., sold closer to 50,000 tickets for the first five-city Canadian leg of his smash Notorious arena tour.

“It seems obvious now,” says Sammy, “but producers failed to realize how many people in Montreal understand both languages.” And, more importantly, would pay $30 and up to hear jokes in both.

This year, he toured En français SVP!, a unilingual version of You're Gonna Rire, and he's taking it back on the road this fall; together, both versions of the show have already sold 135,000 tickets in Quebec. Sammy's winning fans outside Quebec, too. In 2012, he sold more than 120,000 tickets around the world; all told, he has played gigs in 30 countries. His Direct From Montreal concert DVD consistently breaks Amazon.ca's top 50 stand-up comedy charts—and there are a lot of stand-up DVDs on the market. (At press time, Direct From Montreal was #20, edging out titles by hugely popular American performers like Louis C.K., Robin Williams and Wanda Sykes.)

The studio is buzzing with people, and all eyes, lenses and lights are on Sammy. Yet this isn't The Sugar Sammy Show. He quietly listens to directions and easily mugs for the camera. He's game. He's polite. But for a guy who makes his living talking—a guy known as much for his tightly constructed jokes as his improvised, merciless roasting of audience members—he doesn't say much. Canada's New King of Comedy isn't holding court. He likes to save it for the stage.

In a corner of the photo studio, a clown sits at a table, twisting balloons into a crown for the king. When the clown heard this gig was for Sammy, he was giddy for days. Air hisses from a canister. Balloons squeak. Some pop. The crown has to be perfect. Discards pile up on the floor, to be peddled later in Old Montreal. What may not be good enough for Sammy can still fetch five bucks from a tourist.

Finally, success. The balloon crown looks magnificent hovering over Sammy's head, held aloft by a hidden assistant. But things go wrong when Sammy tries to actually wear it. It takes two assistants to squeak the entwined balloons over his head. The crown gets stuck, distorted beyond all recognition. Sammy's perfect hair is done no favours. The clown looks sad, but maybe it's just the makeup. The king looks sad, but maybe it's just his face being smooshed by pressurized rubber. Heavy hangs the head being squeezed by a pair of mating boa constrictors.

Sammy loves the craft of honing a joke, of finding the perfect word that just nails it. But for a guy so devoted to precision, he's lax about the rigid language labels that so obsess Quebecers: francophone, anglophone, allophone.

He begins a thought: “As an ethnic person in Quebec, and an anglophone—” Except he's not. Anglophone, that is. His parents moved from India to Canada in the late 1960s, and the Montreal-born Sammy grew up speaking Punjabi at home. (It's still what he speaks with his parents.) English came second and then, as part of Quebec's first Bill 101 generation (the law dictating that French be the primary language of instruction), Sammy learned French beginning in kindergarten. He picked up Hindi, too. All four languages have found their way into his act.

“Yeah, okay, I'm an allophone.” He shrugs. “Those things aren't an issue for me, so they shouldn't be an issue for anyone else.” Growing up in Montreal's immigrant-heavy Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood, where everyone spoke a minimum of three languages, Sammy heard franglais, and more, every day.

“Race, language and colour were never an issue,” he remembers, “except whenever I'd leave the neighbourhood. In the rest of Quebec, I felt like an outsider.” It was that feeling that drew him toward the edgy stand-up comedy of Eddie Murphy, Chris Rock, Martin Lawrence and Dave Chappelle. “I felt those struggles. Not at the same level as being African-American, but I felt it. I could identify with it, and I think my quote-unquote ‘marginal' point of view has been a breath of fresh air.”

This is what fresh air sounds like when it blows over the ashes of the 1995 Quebec separatism referendum: “For me, there are two types of Quebecers: the ones who are educated, cultured and well raised—and then there are those who voted ‘yes.'”

Sammy stifles a yawn as the camera shutter clicks. He admits that a big part of keeping his boyish looks is getting eight hours of sleep every night. “But it's not easy,” says Sammy, who still “does and doesn't” live with his parents. (He recently rented a condo but uses it more as an office and rehearsal space.)

His parents love what he does (“There's no way you're leaving their house without watching a Sugar Sammy video, no matter who you are”) and he loves them. “I spend a lot of time with my parents,” he says proudly, “more than 99.9 per cent of men my age. It's not a cultural thing. I'm just very attached to them. I'm blessed.” They've unwittingly supplied him with a lot of material (and, he says, love showing up in his act) and even helped him rewrite jokes for his 2010 and 2013 India tours. Sammy even insists that, of his parents, brother and sister, he's the least funny. “I'm just the only one crazy enough to get on stage.”

Life with mom and dad is rewarding. It's just not conducive to Sammy getting his precious eight hours.

“My parents watch cricket and Bollywood so loud—and argue about their Indian soap operas—that it wakes me up in the morning. I have to get my rest on the road.”

Sammy says stand-up will always be his great love, but he's not immune to acting's siren call. After studying with Jacqueline McClintock, the late acting coach who also worked with Mad Men's Jessica Paré, Sammy temporarily moved to Hollywood in the springs of 2009 and 2010 to take part in every wannabe star's rite of passage: pilot season. Sammy read for six sitcom pilots a day and even scored a few callbacks. Nothing came of it. The experience made him realize if he wanted to land a TV role that really fit who he was, he'd have to write it himself.

Sammy will flex his acting muscle in a new, as-yet-untitled half-hour comedy TV series set to air on Quebec's V network in February. The show is being filmed in French; Sammy's hoping to get the show picked up by an English broadcaster. “It's single-camera, no laugh track, no studio audience,” he says, citing pseudo-reality British comedies The Office and Extras as influences. “And written my way.” Well, written his way and the ways of his co-star, comedic actor Simon-Olivier Fecteau, and the young-adult novelist India Desjardins. The two comics play fictionalized versions of themselves, an odd couple made up of “one white, pure laine Québécois and an Anglo from an immigrant family. It's about all the trouble these two single guys get into—and how they make their friendship work despite their differences on every level: political, social and economic.”

Sammy has been building up tosomething, deepening his fan base in Quebec while widening it around the world. He's shortlisted for the Canadian Comedy Awards' Person of the Year, which will be announced on October 6. If he wins, he'll join the ranks of CCA-winning stand-ups like Russell Peters and Brent Butt, two next-level Canadian comedy stars whose careers could serve as a peek into Sammy's future. Even though he's playing theatres and not huge arenas like Peters, Sammy's selling comparable numbers of tickets. Sammy's the same age Butt was when he parlayed his own stage act into the career-altering prairie sitcom Corner Gas. And yet, Sammy may not be the new Russell Peters. He may not be the new Brent Butt. Because Sammy may be something bigger.

With apologies to Justin, Sugar Sammy may very well be the new Pierre Trudeau.

But, like, of comedy.

Consider the evidence. Like the former PM, Sammy is charismatic and good-looking. He's bilingual. He's got a strong support base in Quebec (not counting separatists). He's got ambitions that vault over the borders of his home province. And, like Trudeau, he's got a devil-may-care cheeky streak.

Sammy dismisses the idea of entering politics. (“Bad idea. Bad. Idea.”) But he doesn't hesitate to put Canada's most successful political playbook to work in the comedy arena: first you take Quebec, then you take the Rest of Canada. Although Quebec has a fine tradition of stand-up comedians, it has yet to export the comedy equivalent of a Cirque du Soleil or a Céline Dion. There is a hole waiting to be filled. When Sammy shared an awards-show stage with Pauline Marois in 2010, he irreverently volunteered his services as her English translator. What better dry run for pirouetting behind the Queen? With Sammy now booking his biggest Canada-wide tour ever, for 2015—more cities, more dates, larger venues—the prophecy foretold in that most sacred of texts, the Hollywood Reporter, could come true: Sugarmania may be nigh.

Sugar Sammy clutches a taxidermic beaver. It is small. Its tail is split. Its teeth are unspectacular nubs. Death was merely the first indignity. The sad corpse is accompanied by a small plastic bag of loose fur; it is unclear whether these scraps are meant to be applied as touch-ups, or whether one is expected to hoard post-mortem moulting. The stylist, who procured the prop, assures Sammy that of the three available beavers, “this one was the least rat-like.” The other two beavers must have been rats.

The shutter clicks. Sammy cradles the beaver. He holds the beaver aloft while posing heroically on one foot. He sniffs the beaver and makes a sour face. Sammy cycles through the poses: nurture, elevate, denigrate, nurture, elevate, denigrate. Each time he smells the beaver, his lip curls a little more, his eyebrow arches just a touch higher.

“This isn't good,” he says. “It's decomposing.”

The photographer feigns shock. “Sam! Ça, c'est un symbole du Canada!” Sammy draws a line: he refuses to grant this particular specimen metaphorical heft.

“We've got it really good here,” he says. “Canada is still one of the best countries to live in, and I see that by travelling all over the world. Obviously there's room to improve and we can't let things slip, but there's much more to celebrate than to complain about.”

He casts a sideways glare at the foul beaver.

“Canada smells good!” he counters. “I've been to Asia, so I know.”

Another glare.

“And we're not losing fur.”